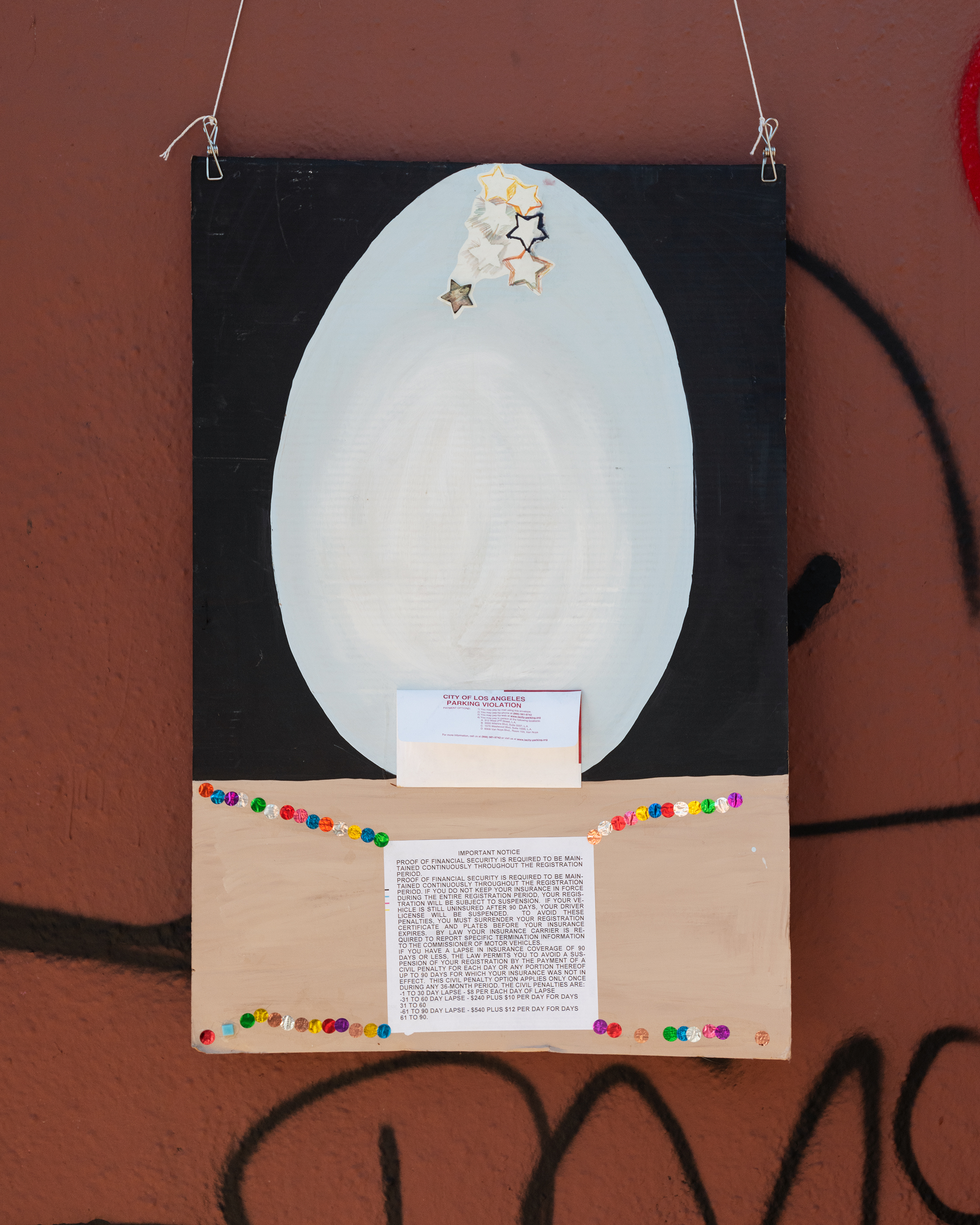

Press Release

by Bill Kitchen

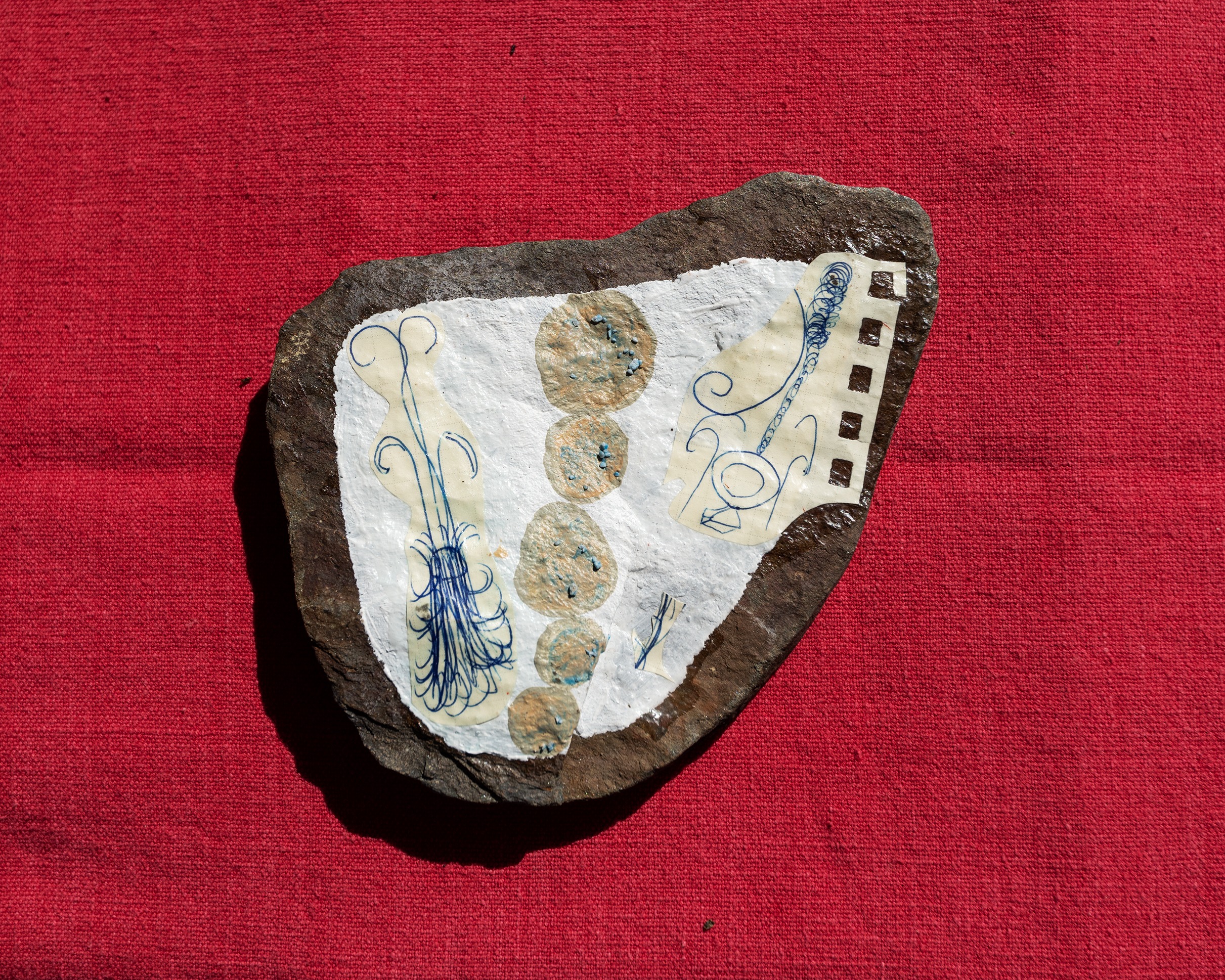

Anthropologists posit the earliest work of art may be older than we once believed: Homo erectus etched a zig-zagging line around the circumference of a mussel shell fossil dated to the Pleistocene.1 Homo sapien glued an Ambien to a popsicle stick.

Hannah is at home in Los Angeles. I’m at the American Museum of Natural History on Central Park West. Practically dressed millennials are taking selfies in the newly opened Gelder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation. A bit like a brushed-concrete termite mound, the new atrium looks wind-sculpted but is actually sculpted by Jeanne Gang, an American architect that sounds like a French or maybe Dutch architect.2 A few organically spaced half-stories of rotunda below, the Spitzer Hall of Human Origins, dedicated in 2007, plays host to a French or maybe Dutch tourist family that all have blonde dreadlocks. In the densely carpeted, neon- acrylic-didactic-plate outfitted exhibition, I find that the dimly lit tableaux of Neanderthal’s occupations feel misplaced in time. Here, it is difficult to imagine that the scene upstairs is happening in the same place at the same time, harder still that the hall’s early hominid subjects and their contemporary viewers could exist on this same timeline. I’m imagining something else entirely: locking eyes with Homo erectus over the din of a crackling bonfire and blushing– his mannequin is well-endowed and kind of cute. The flash of a camera illuminates the matted hairs of Homo habilis and the French or maybe Dutch family in turn as they pose for a photograph.

Early nineteenth century geneticists maintained that ontogeny, the developmental science of an organism, recapitulates phylogeny, the evolutionary science of the organism. They

believed the likeness of human embryos with little fish, then with little salamanders, and eventually with little monkeys proved evolutionary ancestry between all of them.3 As if, since our conception, we’ve embodied everything we’ve ever been on the epochal scale. Consensus has since been reached that this is something like a coincidence. Everything is made from the same stuff, but the developmental histories of our taxonomic group quickly distinguish themselves from the little monkeys’ and are doing so with advancing velocity. The measure at which the human genome has demonstrated accelerating positive selection over the past 40,000 years, a lackluster explanation for the gulf of difference between ourselves and our relatively recent hominid ancestors, has scarcely given us time to process the loss of early human ways of life at the hand of behavioral modernity. The prominence of juice reward mechanism4 and monkeys passing blunts5 on the timeline may be a cultural project of grief– the collective generational outcry for some theological rationale for it all rings over it like an Aboriginal death wail. However, the ontogenetic organization of an individual life as the movements which embody the unique history of its own making, from monkey to Mommy, allows space for the divine. You may be a child of God. You are also a monkey. The monkeys are extracting beetles from each other’s scalps and eating them. The monkeys are walking around unaccompanied in an Ikea in Ontario, Canada.6 The monkeys wear wired headphones; they look like Bella Hadid.7 The monkeys go to work every morning and eat cauliflower rice bowls on their lunch breaks. In this anxious state of human evolution, it is perhaps a narrowness between man and ape that produces such disquiet.

I’m a Monkey makes available some access to our most human instincts. Science is Real but Feelings are Facts. Hannah is an artist I know to constantly reorganize their material life with chimplike fastidiousness. An ontogeny of artistry is revealed in turn.

Hannah Tishkoff (they/them) (b. Los Angeles, 1996) received a BFA from Oberlin College, and has since worked with Bread and Puppet, exhibited at the The Museum of Everyday, and is < 2% Neanderthal.