It’s Not Delivery

February 15th - 23rd, 2025

Jake Tobin

Press Release

by Barrett White

The Saturday Night Live skit “Almost Pizza” (Season 37, 2012) takes place in a suburban kitchen, set-dressed with modern appliances and all the trappings of an upper middle class American lifestyle. The matriarch, played by Kristen Wiig, places what appears to be a pepperoni pizza onto the marble-topped kitchen island. A pizza cutter, plates, utensils, and wine glasses sit nearby, at the ready for a family meal. The pizza itself is visually stereotypical: almost a clip art Platonic ideal, seemingly pulled directly from a DiGiorno advertisement. Bill Hader, the conventional father figure, enters, as if stepping out of the pages of the L.L. Bean catalog, exclaiming “Mmm, pizza! I didn’t hear the delivery guy pull up.” Wiig, cheery, replies: “That’s because it’s not delivery…and it’s not exactly pizza, either. It’s Almost Pizza.”

Hader’s character persists, questioning his wife about the true nature of the pizza; however, she is steadfast, encouraging him to eat it. He notices it’s becoming hotter as it sits. When their daughter (Nasim Pedrad), clearly less concerned, grabs a slice, Hader slaps it from her hand. The family watches on, horrified, as the pizza shatters on the ground like glass (complete with sound effect), reconstitutes itself through a sort of plasmatic metamorphosis, then crawls across the floor and underneath the refrigerator, chittering like a small animal. While the family shrieks and recoils in fear, the announcer tells us: “If it’s Almost Dinner, it's Almost Time for Almost Pizza! The thing that’s much like pizza, roughly speaking. From Pfizer.”

“Almost Pizza” is a reworking of a previous SNL skit, called “That’s Not Yogurt,” which first aired in 1992 and featured Kevin Nealon and Victoria Jackson. A parody of “I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter!” commercials, the couple is plagued by a taunting voiceover who evades revealing the reality of Nealon’s would-be dairy snack. Arguably, though, “Almost Pizza” is the more successful of the two, turning the pseudo-product into something zombie-like, animated and threatening, violating the domestic space with surreal unheimlich.

Jake Tobin’s work is preoccupied with the almost, the sorta-kinda, the maybe not quite. Kinda disorienting, sorta upsetting, and assuredly funny, It’s Not Delivery offers the most comprehensive exhibition of Tobin’s work to date, here spanning animation, sculpture, drawing, and painting. Through an array of cultural detritus, Tobin demonstrates that the credo “everything is not what it seems” is default, embedded in everything from Coke cans to Tesla interiors.

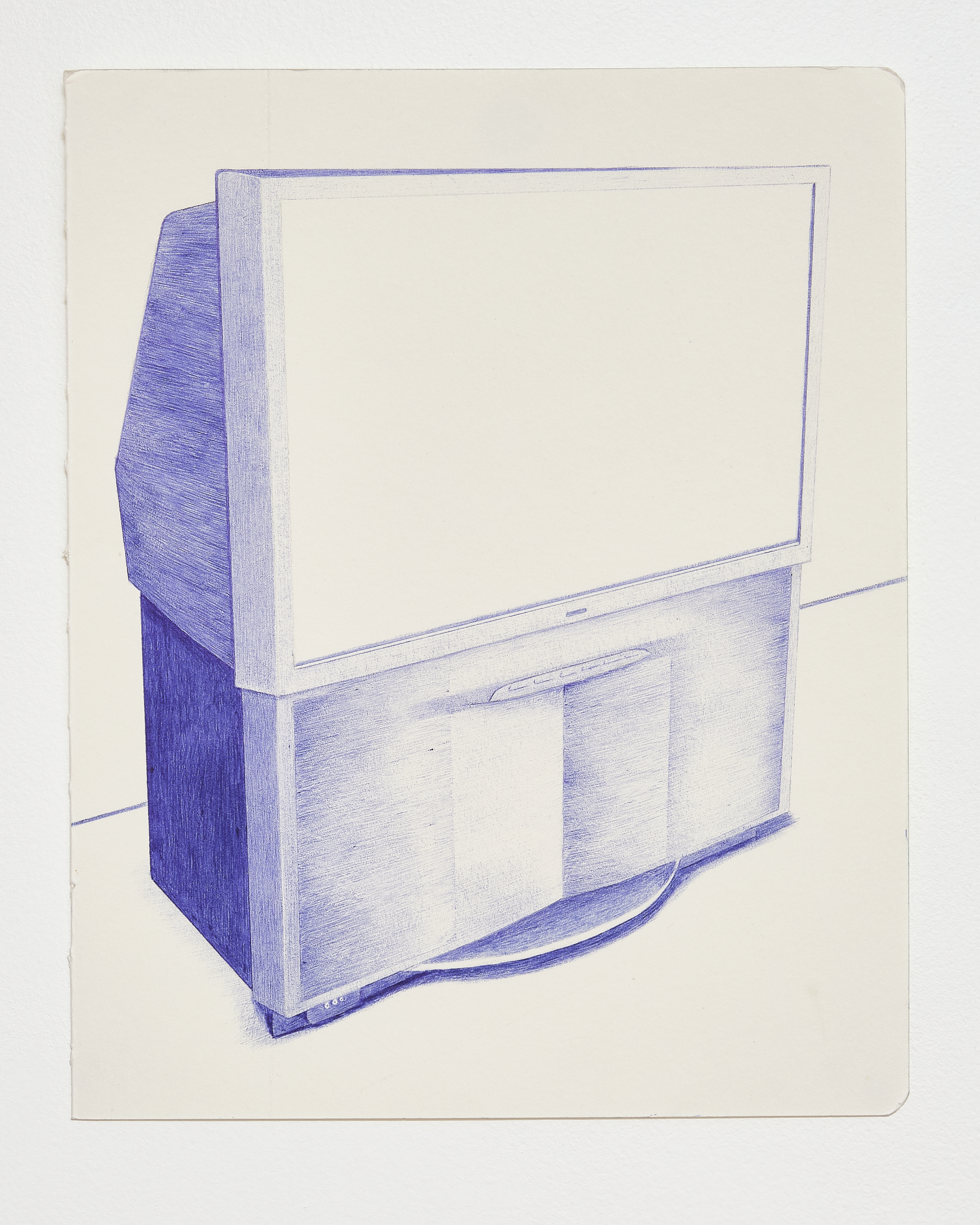

Tobin embraces the garden variety, and this can be seen in his inclination toward familiar yet offbeat early 2000s imagery as well as his choice of materials. His ink drawings are described as “bic on paper,” emphasizing their pedestrian mundanity, and depict things like televisions, gravestones, pots of boiling water, crying fathers, vloggers, and voyeuristic small greys. The gloppy acrylic of “Fountains of Wayne Knight Errant” (2023) smears together pop punk, Seinfeld’s Newman, and the Jeopardy! clue board. His oil paintings are more refined, while still giving us a dose of the nostalgic and partially-remembered: a bedroom with motocross wallpaper, a backyard screening of The Matrix with one hauntingly lonesome folding chair.

Perspective—what we see, what the artist sees—has an outsized presence, and Tobin seeks to tweak ours. The meta-framing of “Untitled (Effective Altruist Orgy)” (2024), in which we are offered the artist’s POV of a painting of a painting on an easel, framed and surrounded by other paintings in the show, is reminiscent of a computer screen overloaded by open browser windows. The perspectival switcheroo is explored further in the video “POV” (2025), which brings together the pieces from this exhibition in a 3D-rendered bedroom decorated with wall-mounted dirt bike wheels and harshly lit by work lights propped atop precariously-stacked Amazon delivery boxes. Within this ambiguous digital stand-in for a gallery space, Tobin mediates his own set of references, stringing things together in complex webs of electric cords and red wire. Coke cans litter the room, a duck is here for some reason, and as the camera spins, pans, and zooms we eventually settle on Sparky, sitting in front of a Sony TV, watching a hand-drawn animation that features his own demise.

Sparky, an anthropomorphized cartoon bundle of dynamite, is Tobin’s trickster god. A cheeky homunculus for contemporary American reality, Sparky’s fuse—and the threat of its lighting—persists as a symbolic and endearing punchline. In “Time in a Bottle Lane” (2022), Sparky’s fate is sealed by his nemesis: Traff, a malfunctioning streetlight fussing with his own spazzing fuses who delivers the final “spark” to send our ill-fated protagonist into combustion.

However, in “Snip” (2023), Sparky lounges in a field, in sleepy repose, a fluffy cloud above him transformed to a dreamy thought bubble in which he imagines a disembodied hand wielding scissors, at the ready to snip away his existential burden. Tobin delivers no release for Sparky here. He is, like us, trapped in a tragicomic limbo between neuter and self-detonation.

Jake Tobin (b. 1991, Worcester, Massachusetts) is a self taught artist born to a family of tradesmen and teachers. He was raised in rural Florida and spent his childhood in the world of motorcross with his older brother, playing the national anthem on the saxophone to open races. He left home, dropped out of school, and made music throughout his twenties, sustained by learning computers. He has worked as a contract engineer for 13 years designing and building meteorology software and online card games. He hates technology and interfaces. His work tends towards a visionary tradition, citing spontaneous transmission and coincidence as primary sources. He uses drawing, painting, sculpture, video, 3D, and software to transcribe images, prioritizing unknowing and beauty through accident, recombination, and a careful false realism. He currently lives in Brooklyn.

This is his second show in Los Angeles following ‘Baby Stuff’ at Scribble. Other recent exhibitions include ‘Acorn Reality’ at Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art and NADA Paris. Recent publications include Ferroschematics (Random Man Editions, 2024) and Assembly (Inpatient Press, 2024).